Confident Learning: Label errors are imperative! So what can you do?

What makes deep-learning so great, despite what you may have heard, is data! There is an old saying, that sums it up pretty well:

The model is only as good as the data!

Which brings us to the real question, exactly how good is your data? Collecting ground truth/training datasets is incredibly expensive, laborious, and time-consuming. The process of labeling involves searching for the object of interest and applying prior knowledge and heuristics to come to a final decision. A decision to represent if the object (of interest) is present and if so, annotate it to provide extra information like bounding box, and segmentation mask.

There are several factors at play in this process that leads to error in the dataset. The question is what can we do about it? In this post, I will touch on some of the reasons why labeling error occurs, why the errors in labels are imperative, and what are the tools and techniques one can use to manage errors in the label datasets. Then, I will dive into the detail of confident learning. I will also demonstrate the use of cleanlab, a confident learning implementation [1], to easily find noise in the data.

Disclaimer: Before diving into the details, I would like to acknowledge that, at the time of writing this post, I am not affiliated with or sponsored by cleanlab in any capacity.

This post is broken down into the following sections:

- Reasons for labeling errors

- Labeling efficiency tricks that increase the risk of labeling errors

- Errors in labels are imperative

- Exactly, what is Confident learning?

- Hands on of label noise analysis using cleanlab for multi-label classification

- Conclusion

- References

Reasons for labeling errors

Let’s first look at some of the reasons why errors in the labels may be present. One broad class for such errors is tooling/software bugs. These can be controlled and managed using good software best practices like tests covering both software and the data. The other class of errors is the one where the mistakes are coming from the labelers themselves. These are incredibly harder issues to track. Because labelers are the oracle in this process of deep learning after all! If we don’t trust them, then who do we trust?

There is a very interesting work by Rebecca Crowley where she provides a detailed chart of a range of reasons why an object (of interest) may be missed while searching in a scene or also why a wrong final decision may be made by them [4]. Some directly impacting labeling in my view are:

- Search Satisficing: The tendency to call off a search once something has been found, leading to premature stopping, thus increasing the chance of missing annotations[4]. This more applies to scenarios where more than one annotation is needed. For example, multi-label or segmentation annotation (dog and pen are in the image but the labeler only annotates for the dog and does not spend enough time to spot the pen and capture in labels).

- Overconfidence & Under-confidence: This type of labeling error relates to one’s feeling-of-knowing [4] that is over or underestimated.

- Availability: There is an implicit bias in annotating it wrongly if something is frequently occurring or rarely occurring [4]. It is particularly true for challenging labeling tasks. For instance, if the cancer prevalence rate in a location is 0.01%, then the labeler, when labeling a not-so-straightforward case, is more likely to mark a non-cancer than cancer.

- Anchoring/Confirmation bias: When a labeler makes a pre-emptive decision [4] about a labeling task outcome and then looks for information to support that decision. For example, believing they are looking at a cancerous case, they start to search for abnormality in the image to support the finding that this case is cancer. In this unfair search/decision process, they are more likely to make mistakes.

- Gambler’s Fallacy: When they are encountered with a repeated pattern of similar cases, then they are likely to deviate and favor an outcome that breaks that pattern [4].

- Amongst all these, Cognitive Overload is also a valid and fair reason for errors in labels.

Labeling efficiency tricks that increase the risk of labeling errors

Given the process to procure a labeling dataset is expensive, some clever tricks and techniques are occasionally applied to optimize the labeling funnel. While some focus on optimization through labeling experience such as Fast Interactive Object Annotation[5], other techniques focus on using auto-labeling techniques to reduce the labeling burden a bit to aid the labelers. Tesla has a very powerful mechanism to realize auto-labeling at scale as talked about in the 2021 CVPR by Karpathy. They sure have the advantage of having feedback (not just the event that’s worth labeling but also what did the driver do or if that led to a mishap). It’s an advantage that not all deep-learning practicing organizations have! Impressive nonetheless! Then we also have the weakly supervised class of training regimes that I won’t go into detail about (perhaps a topic for another day)!

The thing is, the cleverer tricks you employ to optimize this process, the higher the chances of error in your dataset. For instance, using the model in the loop for labeling is being increasingly used to optimize the labeling process (as detailed in this presentation), as an auto-labeling/pre-label trick, wherein predicted labels are shown to the labelers and the labeler only fine-tunes the annotation instead of annotating from the get-go. This process has two main challenges:

a) It may introduce a whole gamut of bias in labels as discussed above in (Reasons for labeling errors.

b) If the model is not on par with human labelers, the labor, and boredom of correcting a garbage prior label increase the risk of errors in the dataset. This is a classic case of cognitive overload.

If this example was not enough, let’s take a case of auto labeling using ontology/knowledge graph. Here, the risk of error propagation is too high if the knowledge encoded in the ontology/knowledge graph is biased. For example, if it’s an ocean water body it cants be a swimming pool. Because well, contrary to common knowledge ocean pools do exist. Or if it’s a house it’s not a waterbody - because you know lake houses do exist!

Ocean Pool/Rock Pool @Mona Vale NSW AU (Image is taken from the internet! @credit: unknown)

Errors in labels are imperative

Given the challenges discussed so far, It is fair to say that errors are imperative. The oracle in this process are labelers and they are only just human!

I am not perfect; I am only human

Evidently, there is an estimated average of at least 3.3% errors across the 10 popular datasets, where for example label errors comprise at least 6% of the ImageNet validation set 2.

Assuming, human labelers will produce a perfectly clean dataset is, well, overreaching to say the least. If one cares, one can employ multiple labelers to reduce the error by removing the noise through consensus. This is a great technique to produce a high-quality dataset but it’s also many times more expensive and slow thus impractical as standard modus-operandi. Besides being expensive, this does not guarantee a clean dataset either. This is evident from Northcutt’s NeurIPS 2021[2] work on analyzing errors in the test set of popular datasets that reported order of hundred samples across popular datasets where an agreement could not be reached on true ground truth despite looking at collating outcomes from labelers (see table 2 in the paper for reference).

For the last few years, I have been using model-in-loop to find samples where there are disagreements in the dataset with the models. Some of the other techniques that I have found useful are leveraging loss functions, as called out by Andrej Karpathy! More recently, I have seen a huge benefit of deploying ontology-based violations to find samples that are either a) labeling errors or b) extreme edge cases that we were not aware of (aka out of distribution [OOD] samples).

When you sort your dataset descending by loss you are guaranteed to find something unexpected, strange and helpful.

— Andrej Karpathy (@karpathy) October 2, 2020

However, I realized I have been living in oblivion when I came across project cleanlab from Northcutt’s group and started digging in a bunch of literature around this exact space! I was excited to uncover all the literature that proposed the tricks and tips I have been using to date without being aware of them. Well no more!! In the following sections, I will cover what I have learned reading through this literature.

Exactly, what is Confident learning?

All models are wrong, but some are useful!

Confident learning[1] (CL) is all about using all the useful information we have at hand to find noise in the dataset and improve the quality of the dataset. It’s about using one oracle (the labelers) and testing it using another oracle in the build i.e. the model! At a very high level, this is exactly what we have been more generally calling model-in-the-loop!

Learning exists in the context of data, yet notions of confidence typically focus on model predictions, not label quality!1

Confident learning (CL) is a class of learning where the focus is to learn well despite some noise in the dataset. This is achieved by accurately and directly characterizing the uncertainty of label noise in the data. The foundation CL depends on is that Label noise is class-conditional, depending only on the latent true class, not the data 1. For instance, a leopard is likely to be mistakenly labeled as a jaguar. This is a very strong argument and in practice untrue. I can argue that the scene (ie the data) has implications for the labeler’s decisions. For instance, a dingy sailing in water is less likely to be labeled as a car if it’s in water. In other words, would not a dingy being transported in a lorry is more likely to be labeled as a car than when it was sailing on the water? so data and context do matters!

This assumption is a classic case of, in statistics any assumption is fair if you can solve for x!. Now that we have taken a dig at this, it’s fair to say that this assumption is somewhat true even if not entirely.

Another assumption CL makes is that rate of error in the dataset is < 1/2. This is a fair assumption and is coming from Angluin & Laird’s[3] proposed method for the class conditional noise process which is used in CL to calculate the joint distribution of noisy and true labels.

In Confident learning, a reasonably well performant model is used to estimate the errors in the dataset. First, the model’s prediction is obtained then, using a class-specific threshold setting confident joint distribution matrix is obtained; which is then normalized to obtain an estimation of the error matrix. This estimated error matrix then builds the foundation for dataset pruning, counting, and ranking samples in the dataset.

Estimating the joint distribution is challenging as it requires disambiguation of epistemic uncertainty (model-predicted probabilities) from aleatoric uncertainty (noisy labels) but useful because its marginals yield important statistics used in the literature, including latent noise transition rates latent prior of uncorrupted labels, and inverse noise rates. 1.

Confident learning in pictures1.

The role of a class-specific threshold is useful to handle variations in model performance for each class. This technique is also helpful to handle collisions in predicted labels.

What’s great about Confident learning and cleanlab (its python implementation of it) is that while it does not propose any groundbreaking algorithm, it has done something that is rarely done. Bring together antecedent works into a very good technical framework that is so powerful that it rightfully questions major datasets that shape the evolution of deep learning. Their work on the analysis of 10 popular datasets including MNIST is well appreciated. This is also a reminder that we are massively overfitting the entire deep learning landscape to datasets like MNIST, and ImageNet, as they are pretty much, must use the dataset to benchmark and qualify bigger and better algorithms and that, they have at least 3.3% errors if not 20% (as estimated by Northcutt’s group)!

This approach was used in side by side comparison where samples were pruned either randomly (shown in orange in below fig) or more strategically via CL to remove noisy samples only (shown in blue below fig). The accuracy results as shown below. CL is doing better than random prune!

Borrowed from Confident learning1

Following are an example of some of the samples that CL flags as noisy/erroneous, also including the edge cases where a) neither were true and b) Its either the CL suggestion or provided label but unclear which of the two are correct (non-agreement):

Examples of samples corrected using Confident learning2.

CL is not 100% accurate. At the best, it is an effort to estimate noise using an epistemic uncertainty predictor [the model]. Having said that these examples it fails on are quite challenging as well.

Examples of samples Confident learning struggled with!2

Fundamentals

Let’s look at the fundamentals CL builds on and dig in a bit on the antecedent and related works that formulate the foundation upon which Confident learning(cleanlab) is built!

-

As discussed above already, is class conditional noise proposed by Angluin & Laird is the main concept utilized by CL.

-

The use of weighted loss functions to estimate the probability of misclassification, as used in 7, is quite relevant to the field of CL, although it’s not directly used in the CL technique as proposed by the Confident learning framework paper.

-

Use of iterative noise cross-validation [INCV] techniques, as proposed in Chen et. al[8], that utilize a model-in-the-loop approach to finding noisy samples. This algorithm is shown below:

Chen’s INCV algorithm

Chen’s INCV algorithm -

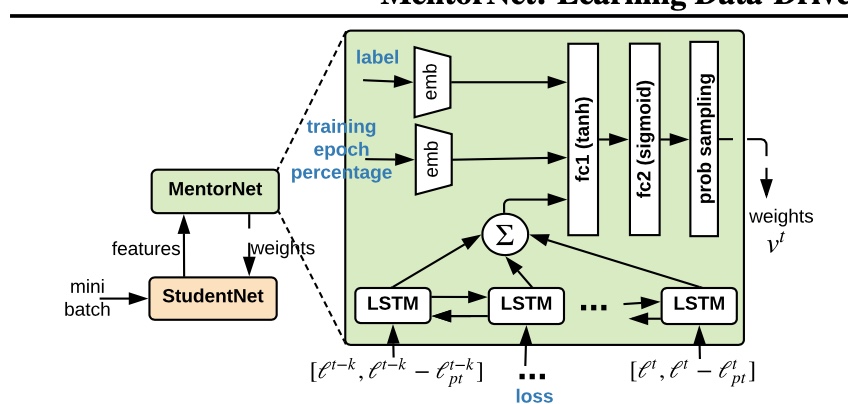

CL does not directly use MentorNet[6]. However, it is very relatable work that builds on a data-driven training approach. In simplistic terms, there is a teacher network that builds a curriculum of easy to hard samples (derived using loss measures) and the student is trained off this curriculum.

MentorNet architecture

MentorNet architecture -

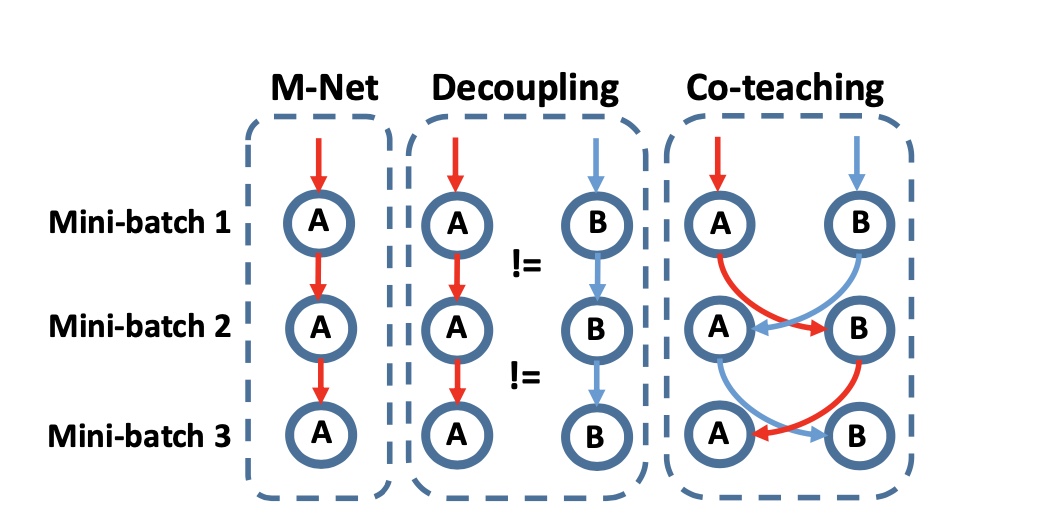

There are other variations to data-driven teaching, one noticeable example is Co-teaching[9] which looks to be teaching each other in pairs and passing the non-noisy samples (calculated based on loss measures) to each other during learning. The main issue Co-teaching tries to solve is the memorization effects that are present in MentorNet[6]. (aka M-Net] but not in Co-teaching[9] due to data share.

Co-teaching approach in contrast with MentorNet aka M-Net

Co-teaching approach in contrast with MentorNet aka M-Net -

The understanding that small losses are a good indicator of useful samples and highly likely correct samples whereas jumpy, high loss producing samples are, well, interesting! They can be extreme edge cases or out-of-distribution samples or also can indicate wrongness. This only holds for reasonably performant models with abilities at least better than random chance if not more!

Limitations of CL

One thing that CL entirely ignores about label errors is when one or more true label is entirely missed. This is more likely to happen in multi-label settings and even more complex labeling setting like segmentation or detection than in multi-class classifications. For example, if there is a TV and water bottle in an image and the only annotation present is for the TV, and the water bottle is missed entirely! This is currently not modeled in CL as relies on building a pairwise class-conditional distribution between the given label and the true label. If the given label was a cat but the actual label was the dog for example. The framework itself does not allow it to model for the missing label when a true label is present.

Pairwise class-conditional distribution as proposed in CL also limits its use in multi-label settings. Explicitly when multiple labels can co-exist on the same data. For example, both the roof and swimming pool can be present in the image and they are not necessarily exclusive. This limitation comes from pairwise (single class gives vs single class predicted) modeling. This is different from say Stanford Car Dataset where make and model are predicted as multiple labels but they are exclusive ie a vehicle can be ute or hatchback but that is exclusive to it being made by Toyota or Volvo. Exclusivity in this case allows for modeling Pairwise class-conditional distribution. These are more multi-label multi-class modeled using multi-headed networks. True multi-label datasets can’t be modeled like these pairwise joint distributions. They can perhaps be modeled using more complex joint distribution formulations but that would not scale very well. Confident learning[1] as it stands currently is a computationally expensive algorithm with an order of complexity being O(m2 + nm).

Having said these, it is probably something that is not explained in the literature as it seems that cleanlab itself supports multi-label classification. Conceptually I am unclear how multi-label works given the said theory. The support for multi-label is developing as issues are being addressed on this tool 1,2.

Hands on of label noise analysis using cleanlab for multi-label classification

Now that we have covered the background and theoretical foundations, let’s try the confident learning out in detecting label noise using its implementation cleanlab. Specifically, I will use multi-label classification given the uncertainty around it (as discussed above)!. For this hands-on, I will use MLRSNet dataset. This spike is built using ResNet as a multi-label image classifier predicting 6 classes that can co-exist at the same time. These classes are ['airplane', 'airport', 'buildings', 'cars', 'runway', 'trees'] and derived off MLRSNet subset - i.e. only using airplane and airport.

The source code and this notebook for this project is label-noise Github repository. The notebook checks how well cleanlab performs in detecting label noise and identifies out-of-distribution samples, weird samples, and also errors!

Model info

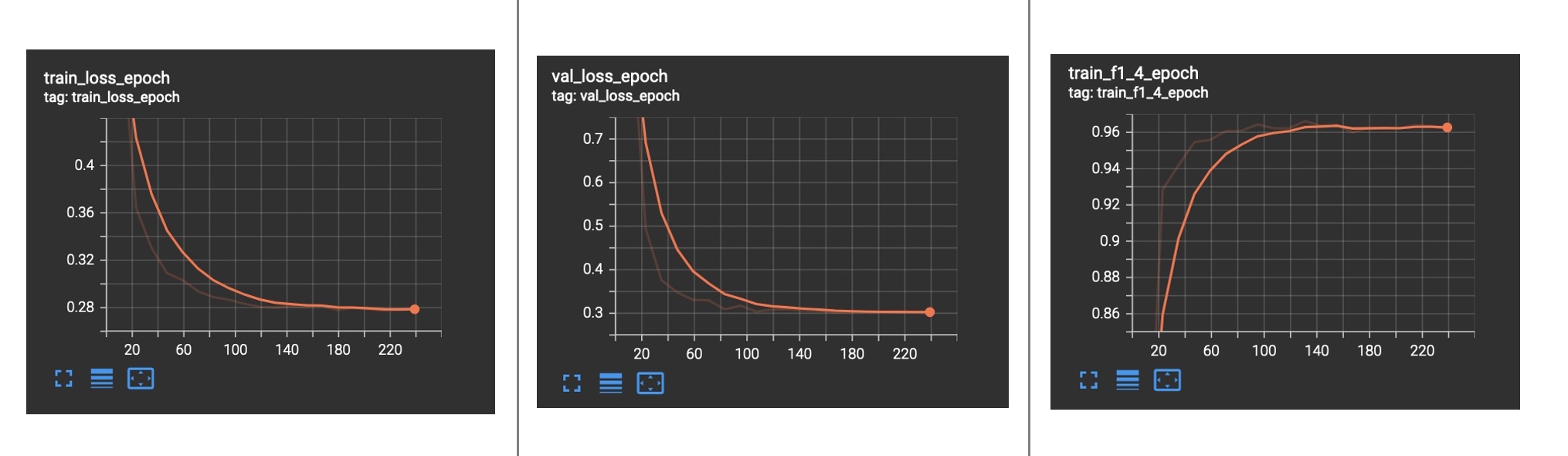

Train and validation loss from the model trained using label-noise for 19 epochs. Note, for this spike, I opted out of n-fold cross-validation (CV). Using CV can lead to better results but its a not quick.

Training logs for the model used in this exercise (Image provided by author)

Exploration in noise using cleanlab

As shown in this notebook, the filter approach provided a list of samples that were deemed noisy. This flagged 38% of out-of-samples as noisy/erroneous.

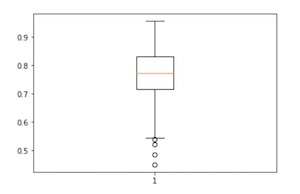

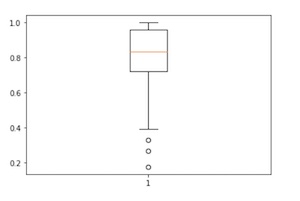

Ranking provided an order in the samples on a 0-1 scale for label quality, the higher the number, the better quality the sample. I looked in get_self_confidence_for_each_label approach for out-of-distribution (OOD) samples and also entropy-based ordering. The distribution for each is as follows:

Confidance order of entropy-based ordering

Confidance order of self_confidence ordering

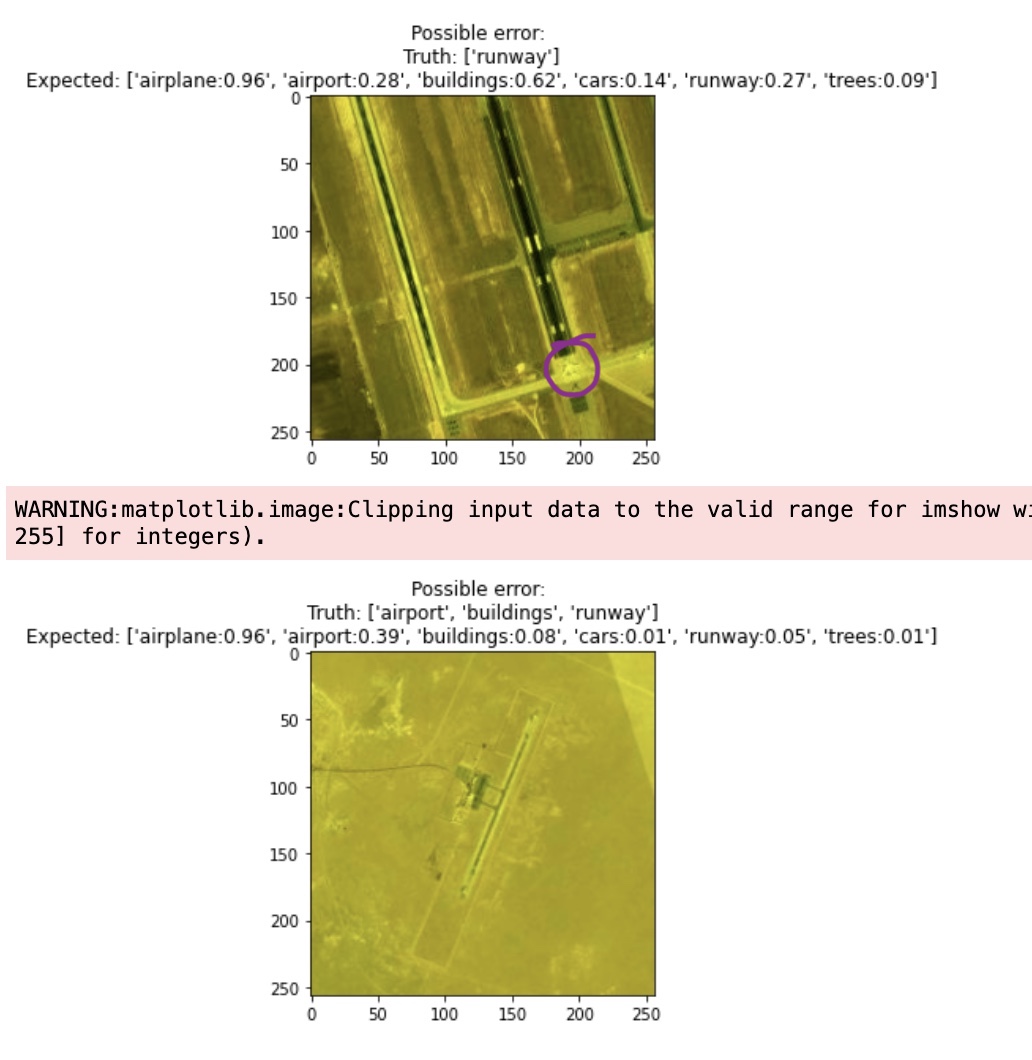

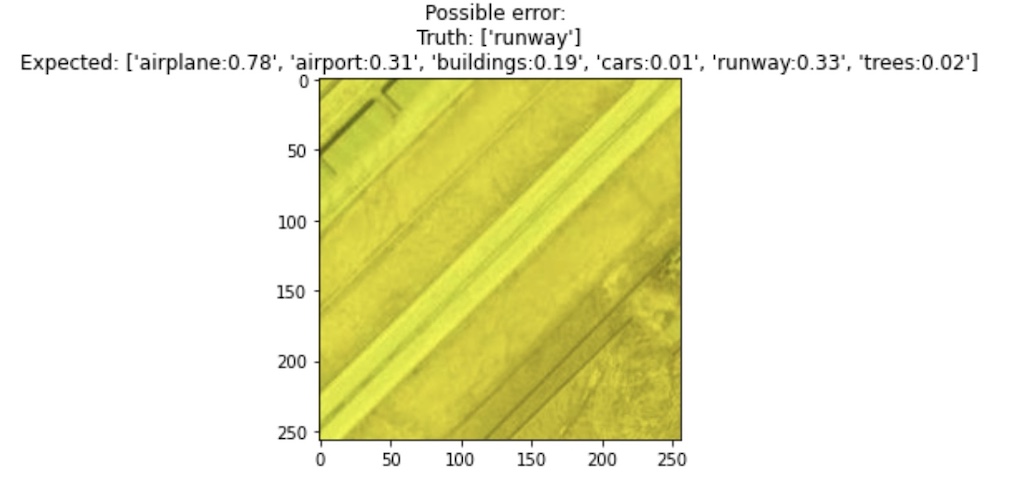

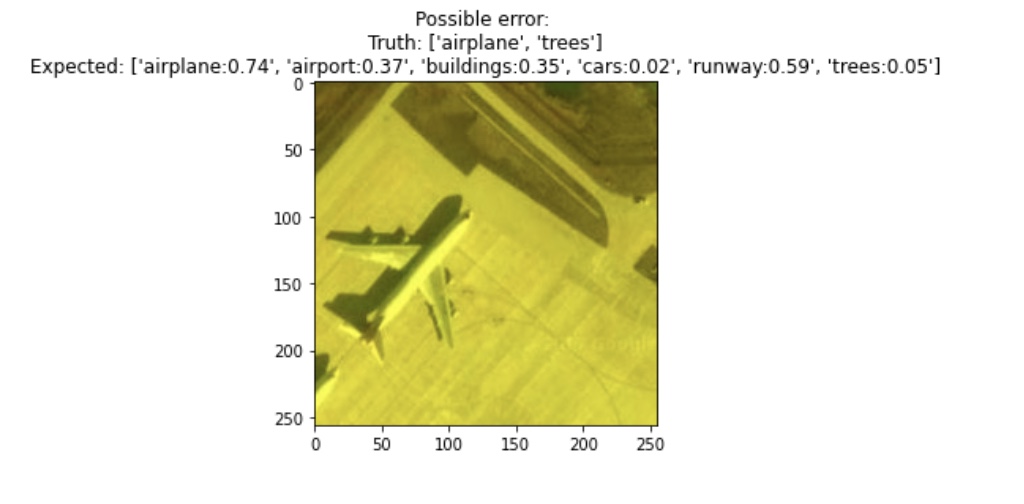

The samples picked as lowest quality or confidence is indeed rightfully chosen. There is an airplane that was missed in the image (shown in the highlighted overlay) and also another sample is OOD!

What’s more interesting is all three methods of filtering, ranked by self-confidence and entropy all flagged these two samples! So we increase the threshold, and while there are false positives (for noise) there is some good example of errors.

| False Positive | True Positive |

|---|---|

|

|

I am not sure if I am following how to interpret the pair-wise count for multi-label, so that’s left for another day!

Conclusion

As discussed in this post, there are several reasons why label errors are unavoidable. While no small-efforts are required to minimize the errors in the dataset, management of the errors in the dataset is also warranted. The management to find noisy data, out of distribution data, or data that represents a systematic flaw (software/tooling issues or issues in the understanding of a concept that defines the target class). Approaches like model-in-loop, or additional information like ontology to find such noises or errors in the dataset are effective techniques. Confident learning provides a solid foundation for analyzing a dataset of noisy or OOD samples — a technique that’s quite effective for multi-class approaches, with the evolving support for multi-label classification. Now, on to cleaning the dataset! Happy cleaning!

References

- C. G. Northcutt, L. Jiang, and I. Chuang. Confident learning: Estimating uncertainty in dataset labels. Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research, 70:1373–1411, 2021. 1911.00068

- Northcutt, C. G., Athalye, A., and Mueller, J. (2021). Pervasive label errors in test sets destabilize machine learning benchmarks. In International Conference on Learning Representations Workshop Track (ICLR). 2103.14749

- D. Angluin and P. Laird. Learning from noisy examples. Machine Learning, 2(4):343–370, 1988. link

- Crowley RS, Legowski E, Medvedeva O, Reitmeyer K, Tseytlin E, Castine M, Jukic D, Mello-Thoms C. Automated detection of heuristics and biases among pathologists in a computer-based system. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2013 Aug;18(3):343-63. doi: 10.1007/s10459-012-9374-z. Epub 2012 May 23. PMID: 22618855; PMCID: PMC3728442. link

- Huan Ling and Jun Gao and Amlan Kar and Wenzheng Chen and Sanja Fidler, Fast Interactive Object Annotation with Curve-GCN. CVPR, 2019 link

- Jiang, L., Zhou, Z., Leung, T., Li, L.-J., and Fei-Fei, L. (2018). Mentornet: Learning data-driven curriculum for very deep neural networks on corrupted labels. In International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML).1712.05055.

- N. Natarajan, I. S. Dhillon, P. K. Ravikumar, and A. Tewari. Learning with noisy labels. In Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), pages 1196–1204, 2013. NurIPS 2013

- P. Chen, B. B. Liao, G. Chen, and S. Zhang. Understanding and utilizing deep neural networks trained with noisy labels. In International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), 2019.1905.05040

- Han, B., Yao, Q., Yu, X., Niu, G., Xu, M., Hu, W., Tsang, I., and Sugiyama, M. (2018). Co-teaching: Robust training of deep neural networks with extremely noisy labels. In Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS). 1804.06872