Review of recent advances in dealing with data size challenges in Deep Learning

The energy and excitement in machine learning and deep learning communities are infectious these days. So many groundbreaking advances are happening in this area but I have often found myself wondering why the only thing that makes it all shine - yes I am talking about the dark horse of deep learning the data is so underappreciated. The last few years of DL research have given me much joy and excitement and I carry hope now that going forward we can see some exciting progress in this space that explore advances in deep learning in conjunction with data! In this article, I summarise some of the recent developments in the deep learning space that I have been blown away by.

Table of content of this article:

- The dark horse of deep learning: data

- Labelled data: the types of labels

- Commonly used DL techniques centered around data

- Challenges in scaling dataset for deep-learning

- Recent advances in data-related techniques

- Conclusion

- References

The dark horse of deep learning: data

Deep learning (DL) algorithms learn to perform a task by building a (domain) knowledge representation by looking at the training data. An early study of image models (classification and segmentation, year 2017) noted that the performance of the model increases logarithmically as the training dataset increases 1. The belief that increasing training dataset size will continue to increase model performance has been long-held. This has also been supported by another empirical study that validated this belief across machine translation, language modeling, image classification, and speech recognition 2 (see figure 1).

*Figure 1: Shows relationship between generalization error and dataset size (log scale) 2 *

So, the bigger dataset is better right? Almost! A theoretical foundation has been laid out in the form of power-law i.e $ \begin{equation} \label{power_law} ε(m) \approx αm^{β_g} \end{equation} $ wherein ε is generalization error, m is the number of samples in the training set, α is a constant property of the problem/DL task, and βg is the scaling exponent that defines the steepness of the learning curve. Here, βg, the steepness of the curve depicts how well a model can learn from adding more data to the training set 2 .(see figure 2) Empirically, βg was found to be between −0.07 and −0.35 despite theory suggesting βg to be 0.5 or 1. Nonetheless, the logarithmic relationship holds. As shown in figure 2, the gain eventually tapers in irreducible error.

*Figure 2: Power Law curve showing model trained with a small dataset only as good as random guesses to rapidly getting better as dataset size increases to eventually settling into irreducible error region explained by a combination of factors including imperfect data that cause imperfect generalization 2 *

This can be attributed to several factors including imperfection in data. The importance of data quality and continually iterating over is touched on in some of the previous talks 1, 2, 3. Data quality matters, and so does the data distribution. The better the distribution of the training dataset is, the more generalized the model can be!

Data is certainly the new oil! 3

So, can we scale the data size without many grievances? Keep in mind, 61% of AI practicing organizations already find data and data-related challenges as their top challenge 4. If the challenges around procurement, storage, data quality, and distribution/demographic of the dataset has not subsumed you yet, this post focuses on yet another series of questioning. How can we train efficiently when data volume grows and the computation cost and turnaround time increase linearly with data growth? Then we begin asking how much of the data is superfluous, which examples are more impactful, and how do we find them? These are very important questions to ask given a recent survey 4 noted that about 40% of the organizations practicing AI already spend at least $1M per annum on GPUs and AI-related compute infrastructures. This should concern us all. Not every organization beyond the FAANG (and also, the one’s assumed in FAANG but missed out on acronym!) and ones with big fat balance sheet will be able to leverage the gain by simply scaling the dataset. Besides, this should concern us all for environmental reasons and carbon emissions implications more details.

The carbon footprint of training a single AI is as much as 284 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent — five times the lifetime emissions of an average car source.

The utopian state of simply scaling training datasets and counting your blessings simply does not exist. The question then is, what are we doing about it? Unfortunately not a whole lot especially if you look at the excitement in the ML research community in utilizing gazillion GPU years to gain a minuscule increase in model performance attributed to algorithmic or architectural changes. But the good news is this area is gaining much more traction now. Few pieces of research since 2020 are very promising albeit in their infancy. I have been following the literature around the use of data in AI (a.k.a data-centric AI) topic very closely as this is one of my active areas of interest. I am excited about some of the recent developments in this area. In this post, I will cover some of my learnings and excitement around this topic.

Before, covering them in detail, let’s review foundational understanding and priors first:

Labelled data: the types of labels

This post focuses heavily on supervised learning scenarios focussing mainly on computer vision. In this space, there are two types of labels:

- Hard labels

- Soft labels

Traditional labels are hard labels where the value of ground truth is a discrete value e.g. 0 and 1, 0 for no, and 1 for yes. These discrete values can be anything depending on how the dataset was curated. It’s important to note that these values are absolute and unambiguously indicate their meaning.

There is an emerging form of labels known as soft labels where ground through represents the likelihood. By nature these labels are continuous. An example, a pixel is 40% cat 60% dog. It will make a whole lot of sense in the following sections.

Commonly used DL techniques centered around data

Data augmentation and transfer learning are two commonly used techniques in deep learning these days that focus on applying data efficiently. Both these techniques are heavily democratized now and commonly applied unless explicitly omitted.

Data Augmentation

Data augmentation encompasses a variety of techniques to transform a datapoint such that it adds variety to the dataset. The technique aims to keep the data distribution about the same but add richness to the dataset by adding variety. Predominantly, the transformation via this technique has been intra-sample. Affine transformations, contrast adjustment, jittering, or color balancing are some such examples of data augmentation techniques. Imgaug and kornia are very good libraries for such operation even though all ML frameworks offer a limited set of data augmentation routines.

Data augmentation technique was initially proposed to increase robustness and achieve better generalization in the model but they are also used as a technique to synthetically increase data size as well. This is especially true in cases where data procurement is really challenging. These days, data augmentation techniques have become a lot more complex and richer including scenarios where-in model-driven augmentations may also be applied. One example of this is GAN-based techniques to augment and synthesize samples. In fact, data augmentation is also one of the techniques to build robustness against adversarial attacks.

- Example of augmentation src *

Transfer Learning

Transfer learning is a very well democratized technique as well that stems from reusing the learned representations into a new task if the problem domain of two tasks is related. Transfer learning relaxes the assumption that the training data must be independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) with the test data 5, allowing one to solve the problem of insufficient training data by bootstrapping model weights from another learned model trained with another dataset.

*Figure 3: Training with and without transfer learning 6 *

With transfer learning, faster convergence can be achieved if there is an overlap between the tasks of the source and target model.

Dimensionality reduction

Dimension reduction techniques are also applied to large datasets:

These techniques are categorized into two:

- Ones that seek to preserve the pairwise distance amongst all the samples in the dataset. Principal component analysis (PCA) is a good example of this.

- Ones that preserve the local distances over global distance. The techniques like uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) 23 and t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) 24 fit in this category. UMAP arguably preserves more of the global structure and is algorithmically faster than t-sne. Both T-SNE and UMAP use gradient descent for arriving at the optimal embeddings.

These techniques in DL space however are mostly used to understand the data and also for visualization purposes. UMAP and T-SNE do better at preserving global structure than other embedding algorithms but are limited. This blog covers the topic more in detail.

Active learning

Active learning is a methodology wherein the training process proactively asks for labels on specific data. It is used more commonly in classical ML techniques, but it has not been very successful in deep learning due to back-propagation. Offline or pool-based active learning has been investigated heavily for use in deep learning but without much groundbreaking success. The use of active learning is not very straightforward either due to the negative impact of outliers on training 25. Pool-based active learning will be covered in the following section in more detail (pruning).

Challenges in scaling dataset for deep-learning

Besides the techniques discussed in previous section, not a lot of investment has been done in the area focussing on data-centric AI. The momentum around data-centric AI is forming a bit recently with Andrew Ng driving data-centric AI efforts through his new startup Landing.AI.

In my view, the following are some of the broad categories of questions that fall under the purview of data-centric AI:

- How to efficiently train with the rapid increase in the dataset? Yann LeCun called out in his interview with Soumith Chintala during PyTorch developer day 2021 that training time of more than 1 week should not be acceptable. This is a very good baseline for practical reasons but if one does not have an enormous GPU fleet at their disposal then this is goalpost is very hard to achieve given current DL practices. So, what else can be done to train efficiently with increased dataset size?

- Are all samples equally important? How important a sample in the dataset is? Can we leverage the “importance factor” for good?

- What role does a sample play towards better generalization? Some samples carry redundant features, so how to deduplicate the dataset when features as in DL are not explicit?

- Data size matters but can we be strategic about what goes in the dataset?

- Cleverly doing this has to do with efficient sampling and data mining techniques. These are the easily solved problem if and only if we know what our targets are. Challenge in DL, as I see it, is what to look for to mine for the best sample? This is not well understood.

- How can we leverage more innate DL techniques like objective functions, backpropagation, and gradient descent to build a slick and effective dataset that provides the highest return on investment.

- Noises in datasets are seen as evil. But are they always evil? How much noise can one live with? How to quantify this?

- How much of a crime it is if data bleeds across traditional train/validate/calibrate/test splits.

- What are the recommendations on the data split for cascade training scenarios?

- How fancy can one get with data augmentation before returns start to diminish?

- How to optimize the use of data if continual learning is observed?

Recent advances in data-related techniques

If we look at humans are learning machines, they have infinite data at their disposal to learn from. Our system had evolved into efficient strategies to parse through infinite data streams to select the samples we are interested in. How our vision system performs foveal fixation utilizing saccadic eye movements to conduct efficient subsampling of interesting and useful datapoint should be a good motivation. Sure we fail sometimes, we fail to see the pen on the table even though it’s right in front of us due to various reasons but we hit it right most of the time. Some concepts of Gestalt theory, a principle used to explain how people perceive visual components (as organized patterns, instead of many disparate parts) are already applicable for better selection of data even if machine models are stochastic parrots. According to this theory, eight main factors, listed below, determine how the visual system automatically groups elements into patterns.

- Proximity: Tendency to perceive objects or shapes that are close to one another as forming a group.

- Similarity: Tendency to group objects if physical resemblance e.g. shape, pattern, color, etc. is present.

- Closure: Tendency to see complete figures/forms even if what is present in the image is incomplete.

- Symmetry: Tendency to ‘see’ objects as symmetrical and forming around a center point. 50

- Common fate: Tendency to associate similar movement as part of a common motion.

- Continuity: Tendency to perceive each object as a single uninterrupted i.e. continuous object

- Good Gestalt: Tendency to group together if a regular, simple, and orderly pattern can be formed

- Past experience: Tendency to categorize objects according to past experience.

Of these, I argue, proximity, similarity, common fate, and past experience are relevant. I even argue on the possibility of applying closure. A recent work by FAIR 22, shows that machine models can fill in the gaps and infer missing pieces correctly by applying minor changes commonly used technique autoencoders. Why I bring this up with so much excitement than GAN-based techniques of hallucination is how easy it is to build and train as compared to GAN.

Masked-Autoencoders showing model inferring missing patches 22

Its been interesting to note that the recent advances towards dealing with the challenges of scaled data are largely inspired by already known deep-learning techniques except they are now applied through the lens of data. Examples like pruning, compression, sampling strategies, and leveraging from phenomena such as catastrophic forgetting, knowledge distillation.

| Technique | How it’s presently utilized in model building | Proposed data-centric view |

|---|---|---|

| Prunning | A specialized class of model compression technique where low magnitude weights are eliminated to reduce the size and computational overhead. | Samples that don’t contribute much to generalization are omitted from the training regime. |

| Compression | A broad range of model compression techniques to reduce the size and computational overhead includes techniques like quantization wherein some amount of information loss is expected. | A broad range of data filtering and compression techniques to reduce size without compromising much on generalization. |

| Distillation | To extract learned representation from a more complex model to a potentially smaller model. | To extract knowledge present in the larger dataset into a smaller synthesized set. |

| Loss function | Also termed as the objective function is the one of core concepts of DL that defines the problem statement. | As shown in 22, and also more broadly can be leveraged to fill in missing information in the data. |

| Regularisation | One of the theoretical principles of DL is applied through various techniques like BatchNorm, Dropouts to avoid overfitting. | Variety of techniques to ensure overfitting applied with data in mind, e.g. Label Smoothing 7,10 |

*Table 1: Summary of techniques that are crossbreed from core DL techniques to also into data-centric DL *

Let’s dive into the details of how these classes of techniques are applied through the lens of data:

1. Regularization

1.1 Mixup

Mixup is a special form of data augmentation technique that looks beyond intra-sample modification and explores inter-sample modification. The idea with mixup is to linearly combine (through convex geometry) a pair of samples to result into one.

$ \begin{equation} x\prime=λx_i + (1−λ)x_j , \ \text{where,} λ ∈ [0,1] \ \text{ drawn from beta distribution, and xi, xj are input/source vector} \end{equation} $

$ \begin{equation} y\prime = λy_i + (1 − λ)y_j , \ \text{where y_i , yj are one-hot label encodings} \end{equation} $

*Figure 4: Sample produced by applying mixup 7 on Oxford Pets dataset *

Mixup 7 in fact seeks to regularize the neural network to favor simple linear behavior in-between training examples. As shown in fig 5, mixup results in better models with fewer missed. Its been shown that mixup increases the generalization, reduces the memorization of corrupt labels, increases the robustness towards adversarial examples 7,8.

Figure 5: Shows that using mixup 7, lower prediction error and smaller gradient norms are observed.

I see mixup as not only an augmentation, and regularisation technique but also a data compression technique. Depending on how frequently (say α) the mixup is applied, the dataset compression ratio (Cr) will :

$ \begin{equation} C_r = 1 - α/2 \end{equation} $

If you have not noticed already, applying mixup convert labels to soft labels. The linear combination of discreet values will result in a continuous label value that can explain the example previously discussed wherein the pixel is 40% cat 60% dog (see fig 5).

1.2 Label Smoothing

Label smoothing 10 is a form of regularisation technique that smoothes out ground truth by a very small value epsilon ɛ. One motivation for this is of course better generalization and avoiding overfitting. While the other motivation is to discourage the model from becoming overconfident. Both 8,10 have shown that label smoothing leads to better models.

$

\begin{equation}

Q_{i} =

\begin{cases} \displaystyle

1 - ɛ & \text{if i == k,} \

ɛ/K & \text{Otherwise, where K is number of classes} \

\end{cases}

\end{equation}

$

Label smoothing as indicated by the equation above does not lead to any visible differences in label data as ɛ is really small. However, applying mixup change visibly changes both source (x) and the label (y).

Applying label-smoothing has no noticeable difference

2. Compression

Compression refers to a broad range of data filtering and compression techniques to reduce size without compromising much on generalization. Following are some of the recent exciting development on this front:

2.1. X-shot learning: How many are enough?

The troubles of high computational cost and long training times due to an increase in the dataset have led to the development of training by a few shot strategies. The intuition behind this approach is to take a model and guide it to learn to perform a new task only by looking at a few samples 11. The concept of transfer learning is implicitly applied in this approach. This line of investigation started with training new tasks by using only a few (handful) samples and explored an extreme case of one-shot training i.e. learning new tasks from only one sample 12,13.

Recently an interesting mega-extreme approach of shot-based learning has emerged - ‘Less Than One’-Shot Learning a.k.a LO Shot learning 11. This approach utilizes soft label concepts and seeks to merge hard label N class samples into M samples where M < N and thus the name less than one! LO Shot-based techniques are a form of data compression technique and may feel very similar to the MixUp technique discussed earlier. However, LO Shot contrary to a convex combination of samples as in Mixup, exploits distance weighted k-Nearest Neighbours technique to infer the soft labels. Their algorithm termed distance-weighted soft-label prototype k-Nearest Neighbours (SLaPkNN) essentially takes the sum of the label vectors of the k-nearest prototypes to target point x, with each prototype weighted inversely proportional to its distance from x. The following figure shows 4 class datasets are merged into 2 samples using SLaPkNN.

Figure LO-Shot: LO Shot splitting 4 class space into 2 points 11.

In my understanding that is the main theoretical difference between the two techniques, with the other difference being mixup only merges two samples into one using a probability drawn from beta distribution combined using λ and 1-λ whereas LO is more versatile and can compress greatly.

I am not saying mixup cant be extended to be more multivariate but that empirical analysis of such approach is unknown; whereas with 11 its been shown SLaPkNN can compress 3M − 2 classes into M samples at least.

The technical explanation for this along with code is available here.

2.2. Pruning

Pruning is a subclass of compression techniques wherein samples that are not really helpful or effective are dropped out whereas selected samples are kept as is without any loss in content. Following are some of the known techniques of dataset pruning:

2.2.1 Coresets

Coreset selection technique pertains to subsampling from a large dataset to a smaller set that almost approximates the given large set. This is not a new technique and has heavily been explored using hand-engineered features and simpler models like Markov models to approximate the smaller set. This is not a DL-specific technique either and has its place in classical ML as well. An example could be using naïve Bayes to select coresets for more computationally expensive counterparts like decision trees.

In deep learning, using a similar concept, a lighter-weight DL model can be used as a proxy to select the approximate dataset 15. This is easier achieved when continual learning is practiced otherwise it can be a very expensive technique in itself given proxy model needs to be trained with a full dataset first. This becomes especially tricky given the proxy and target models are different and also when the information in the dataset is not concentrated in a few samples but uniformly distributed over all of them. These are some of the reasons why this approach is not very successful.

2.2.2 Example forgetting

An investigation 14 reported that some samples once learned are never forgotten and exhibit the same behavior across various training parameters and hyperparameters. There are other classes of samples that are forgotten. The forgetting event was defined as when the model prediction regresses in the subsequent epoch. Both qualitative and qualitative (see fig 6 and 7) analysis into such forgotten samples indicated noisy labels, images with “uncommon” visually complicated features were the main reasons for example forgetting.

Figure 6: Algorithm to track forgotten samples 14.

Figure 7: Indicating how increasing fraction of noisy samples led to increased forgetting events 14.

An interesting observation from this study was that losing a large fraction of unforgotten samples still results in extremely competitive performance on the test set. The hypothesis formed was unforgotten samples are not very informative whereas forgotten samples are more informative and useful for training. In their case, the forgetting score stabilized after 75 epochs (using RESNET & CIFAR but the value will vary as per model and data).

Perhaps a few samples are enough to tell that a cat has 4 legs, a small face, and pointy ears, and it’s more about how different varieties of cats look especially if they look different from the norm e.g. Sphynx cats.

2.2.3 Using Gradient norms

Loss functions are an excellent measure to find interesting samples in your dataset whether these may be poorly labeled or really outlier samples. This was highlighted by Andrej Karpathy as well:

When you sort your dataset descending by loss you are guaranteed to find something unexpected, strange, and helpful.

Personally, I have found loss a very good measure to find poorly labeled samples. So, the natural question would be “should we explore how we can use the loss as a measure to prune the dataset?”. It’s not until NeurIPS 2021, 21 that this was properly investigated. This Standford study looked into the initial loss gradient norm of individual training examples, averaged over several weight initializations, to prune the dataset for better generalization. This work is closely related to example forgetting except that instead of performance measure the focus more is on using local information early in training to prune the dataset.

This work proposes GraNd score of a training sample (x, y) at time t given by L2 norm of the gradient of loss computed on that sample and also expected loss L2 norm termed EL2N (equation below). The reasoning here is that samples with a small GraNd score have abounded influence on learning how to classify the rest of the training data at a given training time. Empirically, this paper found that averaging the norms over multiple weight initializations resulted in scores that correlate with forgetting scores 14 and leads to pruning a significant fraction of samples early in training. They were able to prune 50% of the sample from CIFAR-10 without affecting accuracy, while on the more challenging CIFAR-100 dataset, they pruned 25% of examples with only a 1% drop in accuracy.

$

\begin{equation}

χ_t(x, y) = E_{w_t} || g_t(x, y)||_2 \ \tag*{GraNd eq} \

\end{equation}

$

$ \begin{equation} χ_t(x, y) = E || p(w_t, x) - y)||_2 \ \tag*{EL2N eq} \ \end{equation} $

This is a particularly interesting approach and is a big departure from other pruning strategies to date which treated samples in the dataset independently. Dropping samples based on independent statistics provides a weaker theoretical guarantee of success as DL is a non-convex problem 21. I am very curious to find out how mixup impacts the GraNd scores given it shown (see figure 5b) using mixup leads to smaller gradient norm (l1 albeit).

Results of prunning with GradNd and EL2N 21.

The results from this study are shown in the fig above. Noticeably high pruning is not fruititious even with this approach despite how well it’s doing on CIFAR-10 and 100 datasets. Are we retaining the data distribution when we drop large samples? Mostly not and that is only reasoning that makes sense. And we circle back to how much pruning is enough? Is that network dependent or more a property of data and its distribution? This study 21 claims that GradND and EL2N scores, when averaged over multiple initializations or training trajectories remove dependence on specific weights/networks, presenting a more compressed dataset. If this assertion holds in reality, in my view, this is a very promising finding easing the data-related challenges of DL.

What’s more fascinating about this work is that it sheds light on how the underlying data distribution shapes the training dynamics. This has been amiss until now. Of particular interest is identifying subspaces of the model’s data representation that are relatively stable over the training.

2.3. Distillation

Distillation technique refers to the methodologies of distilling the knowledge of a complex or larger set into a smaller set. Knowledge or model distillation is a popular technique that compresses the learned representation of a larger model into a much smaller model without any significant drop in performance. Using student-teacher training regime have been explored extensively even in the case of transformer networks that are even more data-hungry than more conventional network say Convolution network DeiT. Despite being called data-efficient, this paper employs a teacher-student strategy to transform networks, and data itself is merely treated as a commodity.

Recently, this concept is investigated for use in deep learning for dataset distillation with aim of synthesizing an optimal smaller dataset from a large dataset 17,16. The distilled dataset are learned and synthesized but in theory, they approximate the larger dataset. Note that the synthesized data may not follow the same data distribution.

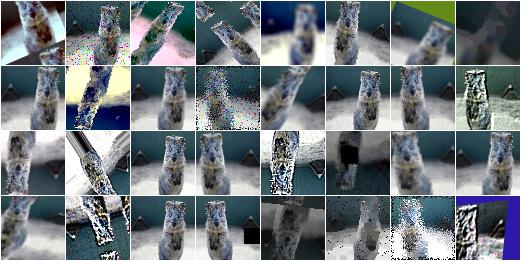

Some dataset distillation techniques refer to their approach as compression as well. I disagree with this in principle as compression albeit lossy in this context, refers to compressing the dataset whereas with distillation the data representation is deduced/synthesized - potentially leading to entirely different samples together. Perhaps it’s the compressibility factor a.k.a compression ratio that applies to both techniques. For example, see figure 13 shows the extent to which distilled images can change.

A dataset distillation 17 paper quotes:

We present a new optimization algorithm for synthesizing a small number of synthetic data samples not only capturing much of the original training data but also tailored explicitly for fast model training in only a few gradient steps 17.

Their problem formulation was very interesting! they derive the network weights as a differentiable function of the synthetic training data and set the training objective to optimize the pixel values of the distilled images The result from this study showed that one can go as low as one synthetic image per category while not regressing too much on the performance. More concretely, they distilled 60K training images of the MNIST digit dataset into only 10 synthetic images (one per class) yields a test-time MNIST recognition performance of 94%, compared to 99% for the original dataset).

Figure 8: Dataset distillation results from FAIR study 17.

Here are some of the distilled samples for the classes labeled at the top (fig 9). It’s amazing how well the MNIST trained on these sets does but CIFAR one misses the mark only being about as good as random (54%) compared to 80% on the full dataset(fig 8 & 9).

Figure 9: Dataset distillation results from FAIR study 17.

Following this work, another distillation technique was proposed utilizing kernel methods - more specifically kernel ridge regression to obtain ε-approximate of original datasets 18. This technique is termed Kernel Inducing Points (KIP) and follows the same principle for keeping the objective function to maximize the approximation and backpropagate the gradients to learn synthesized distilled data. The difference between 18 and 17 is one 17 uses the same DL network while the other 18 uses kernel techniques. With KIP, another advantage is that not just source samples but optionally labels can be synthesized too. In 17, the objective was purely to learn pixel values and thus the source (X). This paper 18 also proposes another technique Label Solve (LS) in while X is kept constant and only label (Y) is learned.

Figure 10: Examples of distilled samples a) with KIP and b) With LS 18.

The CIFAR 10 result from 17 (fig 9) was about 36.79% for 10 samples, with KIP there is a slight gain in performance there given the extreme compression. This raises the question of what is a good compression ratio that can guarantee good information retention. For complex tasks like CIFAR (compared to MNIST), 10 (one per sample) may not be enough given how complex this dataset is comparatively.

Figure 11: CIFAR10 result from KIP and LS 18.

Actually, LO shot technique 11, discussed previously, is also a specialized form of X-shot technique that does dataset distillation. Aside from that, gradient-based techniques for dataset distillation have been actively investigated in the last few years (ref 16,17,18,19,20). Another approach explored siamese augmentation method termed Differentiable Siamese Augmentation (DSA) that uses matching loss and synthesizes dataset through backpropagation techniques 16

Figure 12: Differentiable Siamese Augmentation 16.

Bayesian and gradient-descent trained neural networks converge to Gaussian processes (GP) as the number of hidden units in intermediary layers approaches infinity 20 (fig 13). This is true for convolutional networks as well as they converge to a particular gaussian processes channel limits are stretched to infinity. These networks can thus be described as kernels known as Neural Tangent Kernel (NTK). Neural Tangents library based on JAX an auto differentiation toolkit has been used in applying these kernels in defining some of the recent distillation methods. References 18,20,21 are one such examples.

Figure 13: Infinite width Convolution networks converging to infinity 20.

The authors of KIP and LS techniques 18 explore how to scale and accelerate the distillation process to apply these techniques to infinitely wide convolutional networks 20. Their results are very promising (see fig 14).

Figure 14: KIP ConvNet results 20.

A visual inspection into the distilled dataset from the infinite width CNN-based KIP technique is shown in fig 15. The distillation results are curious, to say the least. In the example, the distilled apple image seems to represent a pile of apples whereas the bottle distilled results into visibly different bottles while still showing artifacts of the original two bottles. While other classes show high order features (with some noise).

Figure 15: KIP ConvNet example of distilled CIFAR set 20.

Figure 16 shows MNIST results, they are not only very interesting but also look very much like mixup (where x and y both are mixed).

Figure 16: KIP ConvNet example of distilled MNIST set 20.

3. So what if you have noisy data

Noises in the dataset are considered a nuisance. Because models hold the compressed form of knowledge represented by the dataset, dataset curation techniques carefully look to avoid noises in datasets.

Noises can be an incredibly powerful technique to fill in the missing information in source/images. For instance, if only part of an image is known then instead of padding the image with default (0 or 1-pixel value), filling in using random noise can be an effective technique avoiding confusion on actual real values that relate to the black or white region. This has held true in my own experience. It was very amusing to note that the forgetting event study 14 in fact looked into adding label noise on the distribution of forgetting events. They added noise in pixel values and observed that adding an increasing amount of noise decreases the number of unforgettable samples (see also figure 7 for their results when noise was used).

Noise coming from randomness is handled very well by DL networks as well. I find the result from 22, shown in figure 17 quite fascinating actually. Looking at how well the model is doing when missing patches are random and how poor it is doing when missing patches are systematic is indicative of how powerful and lame (both at the same time) machines are!

Figure 17: Noisy patches in Masked-AutoEncoder 22.

GradND study 21, looked into the effect of noise on the source itself and performed a series of experiments to conclude that when there is enough data, keeping the high score examples, which are often noisy or difficult, does not hurt performance and can only help.

Conclusion

In summary, the last four years have been incredibly exciting for data in DL space and the year 2021 even more! There is a lot of mileage we can get out of simpler techniques like MixUp but more exciting developments are dissecting the training dynamics and exploring the importance of samples in solving a particular task using DL techniques. Distillation methods are still in the early stages where they work well for simpler datasets but honestly how many real-world problems have simple datasets? Nevertheless, some really exciting development in this space. These techniques can be groundbreaking if the compression methods hold across a wide range of architectures as indicated by 21.

References

- [1707.02968] Revisiting Unreasonable Effectiveness of Data in Deep Learning Era.” Accessed January 3, 2022. https://arxiv.org/abs/1707.02968.

- Hestness, Joel, Sharan Narang, Newsha Ardalani, Gregory Diamos, Heewoo Jun, Hassan Kianinejad, Md Mostofa Ali Patwary, Yang Yang, and Yanqi Zhou. “Deep Learning Scaling Is Predictable, Empirically,” December 2017. https://arxiv.org/abs/1712.00409.

- https://www.wired.com/story/no-data-is-not-the-new-oil/

- https://pages.run.ai/hubfs/PDFs/2021-State-of-AI-Infrastructure-Survey.pdf

- [1808.01974] A Survey on Deep Transfer Learning. Accessed January 5, 2022. https://arxiv.org/abs/1808.01974.

- Transfer Learning. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.146.1515&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- Zhang, Hongyi, Moustapha Cisse, Yann N. Dauphin, and David Lopez-Paz. “Mixup: Beyond Empirical Risk Minimization,” October 2017. https://arxiv.org/abs/1710.09412.

- [1812.01187] Bag of Tricks for Image Classification with Convolutional Neural Networks. Accessed December 30, 2021. https://arxiv.org/abs/1812.01187.

- [2009.08449] ’Less Than One’-Shot Learning: Learning N Classes From M < N Samples. Accessed January 5, 2022. https://arxiv.org/abs/2009.08449.

- [1512.00567] Rethinking the Inception Architecture for Computer Vision. Accessed January 5, 2022. https://arxiv.org/abs/1512.00567.

- [1904.05046] Generalizing from a Few Examples: A Survey on Few-Shot Learning. Accessed January 5, 2022. https://arxiv.org/abs/1904.05046.

- Li Fei-Fei, R. Fergus and P. Perona, “One-shot learning of object categories,” in IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, vol. 28, no. 4, pp. 594–611, April 2006, doi: 10.1109/TPAMI.2006.79. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/1597116

- [1606.04080] Matching Networks for One Shot Learning. Accessed January 5, 2022. https://arxiv.org/abs/1606.04080.

- [1812.05159] An Empirical Study of Example Forgetting during Deep Neural Network Learning. Accessed December 29, 2021. https://arxiv.org/abs/1812.05159.

- [1906.11829] Selection via Proxy: Efficient Data Selection for Deep Learning. Accessed December 29, 2021. https://arxiv.org/abs/1906.11829.

- [2102.08259] Dataset Condensation with Differentiable Siamese Augmentation. Accessed January 5, 2022. https://arxiv.org/abs/2102.08259.

- [1811.10959] Dataset Distillation. Accessed January 5, 2022. https://arxiv.org/abs/1811.10959.

- [2011.00050] Dataset Meta-Learning from Kernel Ridge-Regression. Accessed January 5, 2022. https://arxiv.org/abs/2011.00050.

- [2006.05929] Dataset Condensation with Gradient Matching. Accessed January 5, 2022. https://arxiv.org/abs/2006.05929.

- [2107.13034] Dataset Distillation with Infinitely Wide Convolutional Networks. Accessed January 5, 2022. https://arxiv.org/abs/2107.13034.

- [2107.07075] Deep Learning on a Data Diet: Finding Important Examples Early in Training. Accessed December 10, 2021. https://arxiv.org/abs/2107.07075.

- [2111.06377] Masked Autoencoders Are Scalable Vision Learners. Accessed January 5, 2022. https://arxiv.org/abs/2111.06377.

- [1802.03426] UMAP: Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection for Dimension Reduction. Accessed January 5, 2022. 23. https://arxiv.org/abs/1802.03426.

- Maaten, Laurens van der and Geoffrey E. Hinton. “Visualizing Data using t-SNE.” Journal of Machine Learning Research 9 (2008): 2579–2605. https://www.jmlr.org/papers/volume9/vandermaaten08a/vandermaaten08a.pdf

- [2107.02331] Mind Your Outliers! Investigating the Negative Impact of Outliers on Active Learning for Visual Question Answering.” Accessed January 8, 2022. https://arxiv.org/abs/2107.02331